FAMILIAR SONGS

Many of the great artists of the 19th century gathered great inspiration from the folk cultures of the world. The Brothers Grimm, Leo Tolstoy, and Zoltan Kodaly, to name just a few, used themes from their homeland to inform their work. There's something to the familiar that keeps people coming back to it, remembering times from long ago and associating feelings and knowledge with it. The Greek goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, was the mother of the nine muses, who presided over song, and prompted the memory. Of most interest to us is Terpsichore, who inspired mortals to both choral dancing and song. That the two are considered the specialty of just one muse shows a deep connection between music, language, and rhythmic movement. No wonder that native cultures all have particular blends of those three elements in their traditions and rituals. Something about moving the body helps make music and language more meaningful. The native language of folk songs is intricately woven into their structure, and anyone who reads and memorizes them learns much about the unifying elements of that culture. When language learners sing folk songs, the intonation structures and accent blend perfectly with the music, which gives them a good start on learning a proper accent.

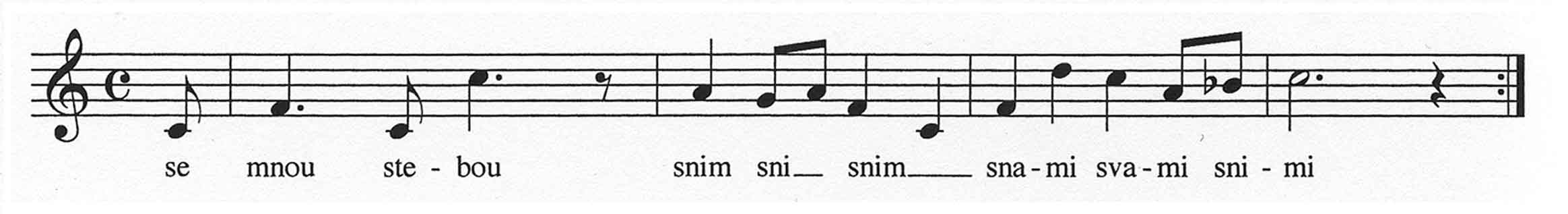

Many language learners reach back to their own cultures for support when the target culture is too overwhelming. They speak the mother language, hum little songs, draw pictures, or daydream about favorite places to make them feel connected again. Harnessing these tendencies for learning the new language is a logical step. In this manner, you will find learners singing a favorite song, but substituting foreign words, often with humorous effect. Fewer will utilize this language learning strategy when a problematic structure of grammar or phrasing comes up. But I was one of the rare learners who thought about the words I was trying to memorize in terms of how they lined up in patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables, like a poem or a song. In a similar fashion to the method by which I wrote the "Ktomu Song," I set out to learn the personal pronouns, in their different cases. I decided to pair them with different prepositions to make phrases (see explanation of case on other page). In the instrumental, or 7th case, each of the personal pronouns (Czech equivalents of I, you, he, she, it, we, you all, they) is paired with the preposition "s" (with) to yield the phrase "se mnou" (with me) and etc. These mini-phrases take up sixteen syllables when considered as a unit.

se mnou stebou snim sni snim snami svami snimi

To organize this sequence musically, I thought of it in a regular 4/4 rhythm. That would mean, accounting for pauses between the words, a structure of four measures comprised of four beats. An existing song, the exciting theme from the 80's television drama "Dallas," matches the intonation of this group of phrases.

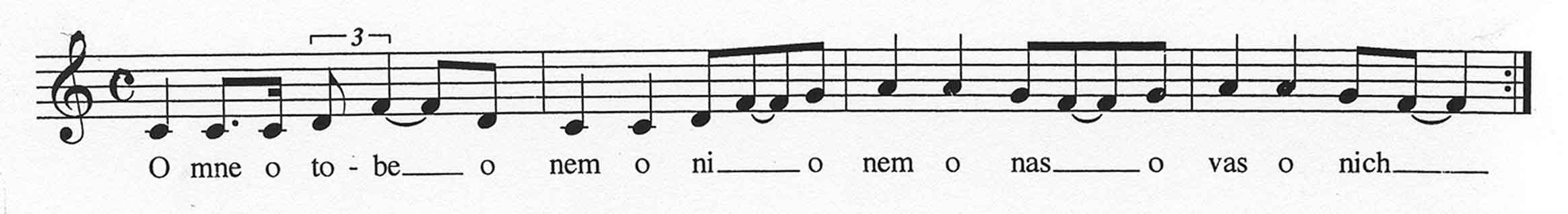

When trying to remember the proper case form, I only had to remember the song, and the right word was there. When I learned the other prepositions that require the same case, I knew how to say many important basic phrases. Along with "Dallas," I also used the song "Old Man River" from the musical "Showboat," and "Red River Valley" for other cases. Following are these new songs.

This means "about me, about you, about him, about her, about it, about us, about you, about them"

Likewise, this means "without me, you, him," and etc.

Language learners can use rhythmic chants to memorize words and phrases. Since rhythm is an everyday part of life, some students may not even realize that they are putting their vocabulary words to rhythm unless it is pointed out to them. Before learners try to integrate this strategy, they need to identify what strategies they have already been using. Many students have success in learning noun endings with rhythm. In order to put some context to the words, I suggest memorizing key words as parts of small phrases. Once I saw a native speaker of Czech put words as the objects of a procession of sentences, putting words in each case one by one. He said: Je hrad, bez hrada, jdi k hradi. Vidim hrad, mluvim o hrade, udelam to hradem. This means: There's a castle, without a castle, go to the castle. I see a castle, I talk about a castle, I do it with a castle. He also counted off on his fingers the number of the case (1,2,3,4,6,7). Putting this organization to phrases is quite helpful. Even when students do not have a piece of paper in front of them, they can still use sentence context, grammar structure, and organization of phrases.

I warn advanced students against the too-profuse use of rhythmic and song mnemonics after initial steps have been made towards understanding and production. Students who still want to sing should begin to learn folk songs, which are very useful in terms of context-based vocabulary usage, colloquialisms, and in their sense of cultural values and ethos. Many traditions borrow folk melodies from each other, so it's possible that there are many songs in the new language that you already know. Old hymns are good examples of this, because as religions spread to other countries, they brought their music with them. Anything that activates the musical and rhythmic intelligence can meaningfully enrich language learning. It's also helpful at some point to translate backwards from the new language into the mother tongue. Incorporating hand gestures also enriches a message, so learning the sign language of that culture may be a method to help learners to remember words or concepts. Looking at pictures is another excellent way to involve more areas of the mind and increase the recall of language input.